For centuries, people across different cultures have shared anecdotes about animals behaving strangely before natural disasters, particularly earthquakes. From dogs barking incessantly to birds fleeing their nests hours before the ground shakes, these accounts have often been dismissed as folklore or coincidence. However, in recent decades, the scientific community has begun to take these observations more seriously, investigating whether there is a biological basis for what appears to be a premonitory ability in the animal kingdom.

The idea that animals can predict earthquakes is not new. Historical records from ancient Greece, China, and Japan document instances of animals like rats, snakes, and weasels fleeing areas days before major seismic events. In 1975, in the Chinese city of Haicheng, officials noted widespread unusual animal behavior, such as cows breaking their tethers and chickens refusing to enter their coops. This, combined with other precursor signs, led to the evacuation of the city just hours before a 7.3 magnitude earthquake struck, saving countless lives. While not all such stories have been scientifically verified, the sheer volume of consistent reports has prompted researchers to look beyond mere superstition.

So, what could explain this phenomenon? One leading hypothesis centers on animals' heightened sensitivity to environmental stimuli that humans cannot perceive. Earthquakes are preceded by the buildup of immense tectonic stress, which can generate a variety of physical and chemical changes in the environment. These include the release of gases like radon, changes in groundwater levels, and the production of low-frequency electromagnetic signals. Many animals possess sensory organs capable of detecting these subtle changes long before the actual quake occurs.

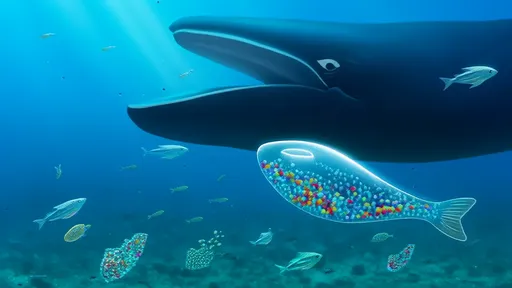

Consider, for example, the ability of many animals to detect infrasound—sound waves with frequencies below the range of human hearing. Elephants, whales, and even pigeons are known to use infrasound for communication and navigation. Before an earthquake, the fracturing of underground rocks can generate significant infrasound emissions. To animals attuned to these frequencies, this might sound like an approaching storm or other large-scale threat, triggering a flight response. Similarly, changes in the Earth's magnetic field, which can occur prior to seismic activity, might be detected by species like birds or sharks that use magnetoreception for migration.

Another potential cue is the release of charged particles, such as positive ions, into the air due to the pressure building up in rocks—a process known as the piezoelectric effect. This ionization of the air can lead to changes in local weather, create unusual atmospheric phenomena like earthquake lights, and may cause discomfort or agitation in animals. Some researchers suggest that these ions could trigger serotonin syndrome in animals, leading to symptoms of anxiety and restlessness. This might explain why pets often become anxious, hide, or try to escape before a quake.

Furthermore, the acute olfactory senses of many animals could allow them to detect gases released from the ground under stress. Radon gas, for instance, is often released from underground before and during earthquakes. While odorless to humans, it's possible that other accompanying gases or changes in air composition are detectable by animals with more sensitive noses, like dogs or rodents. This might signal danger, prompting them to move to safer ground.

Despite these plausible mechanisms, the scientific community remains cautious. A significant challenge is the inconsistency of animal behavior before earthquakes; not all quakes are preceded by widespread animal agitation, and sometimes animals act strangely without any subsequent seismic event. This variability makes it difficult to establish a reliable, causal link. Critics argue that many reports are subject to confirmation bias—people remember the times animals were restless before a quake but forget the many times they were restless and nothing happened.

To address these challenges, researchers have initiated more systematic studies. In one project, scientists attached sensors to farm animals in earthquake-prone regions to monitor their movements continuously. The goal is to collect large datasets of animal behavior and correlate them with seismic activity to identify patterns that might be predictive. Early results have shown promise; in several cases, the animals exhibited collective restlessness hours before detectable tremors. However, these studies are ongoing, and more data is needed to draw definitive conclusions.

Technology is also playing a role in bridging the gap between anecdote and evidence. With the advent of affordable sensors and citizen science platforms, researchers can now gather real-time reports of animal behavior from large populations. Coupled with seismic data, this information could help build predictive models that incorporate biological signals alongside geological measurements. Some envision a future where networks of animal monitors serve as an early-warning system, complementing traditional seismological approaches.

Yet, even if a correlation is firmly established, implementing animal-based prediction systems would face practical hurdles. Animal behavior is influenced by a multitude of factors—weather, predators, human activity—making it noisy data. Distinguishing earthquake-related behavior from other stressors is no small feat. Moreover, ethical considerations arise regarding the welfare of animals used in monitoring programs. Any such system would need to be non-invasive and ensure that the animals are not harmed or unduly stressed by the observation process.

In the meantime, the investigation into animals' seismic sensitivity has broader implications for biology and sensory science. It highlights the remarkable capabilities of non-human species to perceive aspects of the world that are invisible to us. Studying these abilities not only deepens our understanding of animal cognition and sensory biology but also reminds us of the interconnectedness of all life with the physical environment. It is a humbling thought that creatures we often regard as lesser might hold keys to predicting one of nature's most destructive forces.

While we may not yet be able to rely on our pets to warn us of the next big one, the ongoing research underscores a valuable lesson: sometimes, the oldest observations contain kernels of truth waiting to be uncovered by science. The strange behavior of animals before earthquakes continues to captivate both the public and scientists, standing at the fascinating intersection of folklore, ecology, and geophysics. As studies progress, we may find that these ancient stories hold not just cultural value, but practical insights that could enhance our resilience to natural disasters.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025