The question of whether alternative technologies can reduce animal testing is not merely a scientific inquiry but an ethical imperative that has gained significant traction in recent decades. As public awareness grows and technological capabilities expand, the laboratory landscape is undergoing a profound transformation. The core principle of the 3Rs—Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement—has provided a robust ethical framework, pushing the scientific community to seek innovative paths that minimize animal suffering. This movement is driven by a confluence of ethical concerns, regulatory pressures, and the undeniable fact that in many cases, non-animal methods are simply better science.

For centuries, animal models have been the cornerstone of biomedical research, toxicology, and drug development. Their use was predicated on the biological similarities they share with humans, offering a complex, living system to study disease processes and potential treatments. This reliance, however, has always been accompanied by significant ethical dilemmas. The moral cost of inflicting pain, distress, and death on sentient beings weighs heavily, creating a constant tension between the pursuit of human knowledge and the welfare of other species. This ethical unease laid the groundwork for the development of the 3Rs principle, which explicitly champions the search for replacement methods that avoid the use of animals altogether.

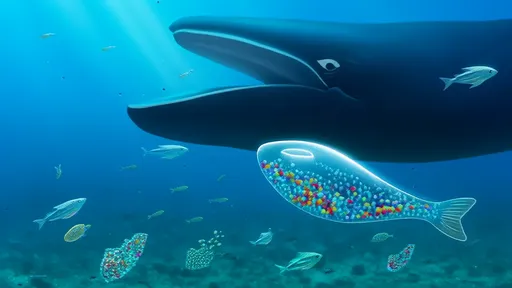

The arsenal of alternative technologies is diverse and rapidly evolving, moving from simple cell cultures to breathtakingly complex human-mimicking systems. In vitro techniques, which involve testing on cells or tissues in a controlled environment, represent the most established category of alternatives. These range from basic two-dimensional cell cultures to more sophisticated three-dimensional organoids and tissue-on-a-chip models. These micro-engineered devices can simulate the functions of entire human organs, such as a lung, liver, or heart, on a chip smaller than a USB stick. They allow researchers to observe human-specific biological responses in a way that animal models, which often metabolize substances differently, simply cannot match.

Another powerful frontier is in silico modeling, which uses advanced computer simulations and artificial intelligence to predict how a chemical or drug will behave in a biological system. By feeding vast databases of existing chemical and biological information into complex algorithms, researchers can now forecast a compound's toxicity or efficacy with surprising accuracy. This computational power enables the virtual screening of thousands of molecules, identifying the most promising candidates for further study and filtering out those likely to fail or be harmful long before they ever reach a living creature. This not only reduces animal use but also drastically cuts the time and cost associated with early-stage research.

Furthermore, advanced imaging technologies and human-based studies offer direct pathways to replacement. Sophisticated MRI, CT, and PET scans can provide intricate details of human disease progression and treatment response in volunteer patients, generating data that is inherently more relevant than that from an animal surrogate. The use of human volunteers in microdosing studies, where minuscule, non-pharmacologically active doses of a drug are administered, allows scientists to track its distribution in the human body with extreme sensitivity. These human-centric approaches are gradually eroding the perceived necessity of animal models for certain types of research.

The impact of these alternatives is already being felt across industries. In the cosmetic sector, a strong ethical consumer movement and subsequent regulatory bans in many countries have virtually eliminated animal testing for finished products. This forced the industry to pioneer and validate a suite of in vitro and reconstructed human skin models that are now considered the gold standard for skin irritation and corrosion testing. Similarly, in regulatory toxicology, there has been a significant shift. Accepted alternative methods now exist for testing eye irritation, skin sensitization, and phototoxicity, leading to the direct replacement of many traditional animal tests like the Draize test. These are not niche applications; they represent a fundamental rewriting of safety assessment protocols on a global scale.

However, the path to widespread adoption is not without its formidable obstacles. The single greatest challenge is validation and regulatory acceptance. To be approved for use in safety assessments, any new alternative method must undergo a rigorous, multi-year validation process to prove it is as reliable, or more reliable, than the animal test it seeks to replace. This process is slow, expensive, and fraught with bureaucratic inertia. Regulatory agencies, often risk-averse, are hesitant to replace long-standing animal-based tests with new technologies without an overwhelming body of evidence. This creates a frustrating catch-22: alternatives need widespread use to generate validation data, but they cannot gain widespread use until they are validated.

Scientific and biological complexities also present hurdles. While organ-on-a-chip technology is revolutionary, creating a fully functional chip that seamlessly integrates multiple organs to accurately mimic the entire human body—a "human-on-a-chip"—remains a monumental task. The human immune system, the intricate gut-brain axis, and complex chronic diseases like cancer or Alzheimer's involve multifaceted interactions that are incredibly difficult to replicate outside a living organism. For these areas, a complete replacement for animal models in the immediate future seems unlikely, though alternatives are increasingly used to reduce the number of animals required and refine procedures to minimize suffering.

Despite these challenges, the momentum is undeniable. Major funding bodies, including government agencies in the United States and the European Union, are actively prioritizing and financing the development of new alternative methods. A powerful driver is the growing recognition of the scientific limitations of animal models. The high failure rate of drugs that show promise in animals but prove ineffective or unsafe in humans underscores a critical flaw in the traditional paradigm. Alternatives that use human cells and genes offer a more direct and potentially more accurate prediction of human outcomes, making them not just an ethical choice, but a scientifically superior one.

In conclusion, the evidence is clear: alternative technologies are not a futuristic fantasy but a present-day reality that is actively reducing and replacing animal experiments. From cosmetics to chemicals, validated non-animal methods are already saving millions of animal lives. The journey is complex, and the complete elimination of animal testing may remain a distant goal for certain complex biological questions. Yet, the trajectory is set. Through continued investment, cross-disciplinary collaboration, and a steadfast commitment to the ethical principles of the 3Rs, the scientific community is steadily building a future where human-relevant science flourishes and animal suffering in laboratories becomes an increasingly rare exception rather than the rule.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025