In the quiet forests of North America, a subtle but profound transformation is underway. The peppered moth, once predominantly light-colored to blend with lichen-covered trees, now wears sooty wings that mirror the industrial grime coating urban bark. This iconic example, documented since the 19th century, represents just the tip of the iceberg in how human activities are fundamentally redirecting the evolutionary pathways of countless species. We are not merely altering habitats; we are becoming architects of evolution itself, often in ways we are only beginning to comprehend.

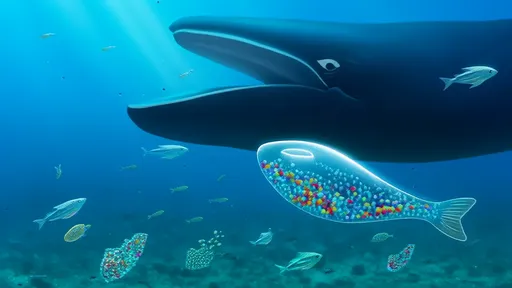

The most direct human influence on animal evolution stems from selective harvesting. For centuries, humans have acted as powerful predators, but unlike natural predators, our hunting preferences are often skewed toward specific traits. The consequences are starkly visible in fisheries worldwide. Intense fishing pressure consistently targets the largest, fastest-growing fish. Over generations, this has created a strong selective pressure against these very traits. The result is a phenomenon known as fisheries-induced evolution: fish populations are now genetically programmed to mature earlier and at smaller sizes. We are, in effect, breeding smaller, slower-growing fish, permanently altering the biology of entire species for the sake of short-term catch yields.

Beyond targeted hunting, the sheer modification of landscapes forces animals to adapt or perish. The fragmentation of forests by roads and agriculture creates isolated islands of habitat. For species like birds or small mammals, this isolation can lead to rapid evolutionary changes. With reduced gene flow between populations, genetic drift and local adaptation accelerate. A bird species separated by a highway may develop a slightly different song to attract mates in its diminished territory, the first step toward speciation. Conversely, the creation of new, human-made environments like cities has given rise to "urban adapters." Creatures like the urban fox or the city pigeon exhibit boldness and cognitive flexibility that their rural cousins lack. They navigate traffic, exploit novel food sources, and tolerate noise and light pollution—a suite of traits that evolution is favoring in the concrete jungle.

Perhaps one of the most insidious drivers of human-induced evolution is pollution. Industrial waste has created environments that would be lethally toxic to most life forms, yet some species are evolving resistance at breakneck speed. The classic case is the pepper moth during the Industrial Revolution, but modern examples abound. In parts of New England, populations of Atlantic killifish thrive in estuaries saturated with dioxins and PCBs—carcinogens that would kill other fish. Genomic studies reveal that this resilience is not mere acclimation; it is a hardwired evolutionary adaptation, with strong selection for specific genetic variants that confer tolerance to the toxic soup. We are inadvertently selecting for "super-resistant" organisms, creating new genetic lineages shaped by our waste.

The introduction of invasive species, often a byproduct of global trade and travel, sets off dramatic evolutionary arms races. When a new predator or competitor arrives in an ecosystem, native species face sudden, intense pressure. In Australia, the introduction of the toxic cane toad decimated populations of native predators that attempted to eat it. However, some species, like certain snakes and birds, are now evolving. Behavioral adaptations, such as learning to avoid the toads, are being followed by physiological ones, like smaller heads that prevent them from eating large, lethal toads. The native fauna is evolving in real time to survive the threat we introduced.

Finally, climate change, the ultimate human footprint, is rewriting evolutionary rules on a planetary scale. As temperatures rise, species are confronted with a new set of constraints. The most obvious response is a shift in range, moving poleward or to higher elevations. But for those that cannot move, rapid adaptation is the only alternative. We are seeing changes in phenology—the timing of life events. Birds are laying eggs earlier, plants are flowering sooner, and insects are emerging earlier in the spring to align with the new thermal reality. Beyond timing, morphological changes are also occurring. Some warm-blooded animals, from mice to birds, are evolving larger extremities—beaks, ears, legs—which help dissipate excess body heat more efficiently, a clear morphological response to a warming world dictated by Allen's Rule.

In conclusion, the narrative of evolution is no longer written solely by the blind forces of nature. Humanity has become a dominant selective agent, pushing, prodding, and reshaping the evolutionary trajectories of the animal kingdom through our harvesting, our structures, our pollution, our introduced species, and our altering of the global climate. These changes are occurring within decades, sometimes even years—a mere blink of an eye in geological time. This awesome power carries with it a profound responsibility. As we continue to reshape the planet, understanding and anticipating the evolutionary consequences of our actions is not just an academic exercise; it is critical to managing and conserving the biodiversity upon which we all ultimately depend. The story of evolution now has a new main character: us.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025