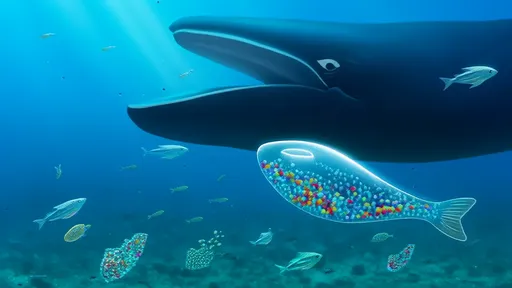

In the vast expanse of our oceans, a silent and pervasive crisis is unfolding—one that begins at the microscopic level and escalates through the entire marine food web. Plastic microdebris, fragments smaller than five millimeters, has infiltrated even the most remote aquatic environments, presenting a complex ecological threat. These particles originate from a variety of sources, including the breakdown of larger plastic waste, microbeads from personal care products, and synthetic fibers from washing clothes. Their small size and persistence make them particularly insidious, as they are easily ingested by the smallest marine organisms, setting the stage for a chain reaction of contamination that reaches the largest creatures in the sea.

The journey of plastic microparticles through the marine ecosystem starts with the foundation of the oceanic food chain: plankton. Phytoplankton and zooplankton, the drifters of the sea, are not only crucial for carbon cycling and oxygen production but also serve as the primary consumers of microplastics. Research has shown that these tiny organisms mistake plastic fragments for food, ingesting them along with their usual diet of algae and detritus. This ingestion can lead to reduced feeding efficiency, energy depletion, and impaired reproductive success. Moreover, the physical presence of plastics in their digestive systems can cause internal abrasions and blockages, ultimately affecting their survival rates and, by extension, the stability of the planktonic community.

As plankton are consumed by small filter-feeders and predatory species, the plastic particles are transferred upward. Krill, small fish like anchovies, and other primary consumers accumulate these microplastics in their gastrointestinal tracts. The implications are severe: studies indicate that microplastics can leach toxic additives, such as phthalates and bisphenol A, into the tissues of these animals. Additionally, plastics act as sponges for hydrophobic pollutants already present in seawater, including pesticides and industrial chemicals like PCBs. When ingested, these toxin-laden particles can cause oxidative stress, inflammation, and cellular damage in marine organisms, compromising their health and behavior.

The contamination does not stop at primary consumers. Mid-trophic-level species, including larger fish, squid, and crustaceans, prey upon these smaller organisms, further concentrating microplastics and their associated toxins through a process known as trophic transfer. For instance, a mackerel that feeds on contaminated krill may ingest hundreds of microplastic particles in a single meal. Over time, this bioaccumulation can lead to higher internal concentrations of plastics and toxins than found in their prey. Laboratory and field studies have documented adverse effects such as liver toxicity, reduced growth rates, and altered feeding behaviors in these species, which not only threatens their populations but also has significant implications for fisheries and human consumption.

At the apex of the marine food web, predators like tuna, sharks, and marine mammals face the greatest risk from biomagnification. These animals consume large quantities of contaminated prey, resulting in the accumulation of microplastics and toxins in their bodies at concentrations orders of magnitude higher than in the water itself. For example, filter-feeding baleen whales, which engulf massive volumes of water to capture krill and small fish, are particularly vulnerable. Necropsies of stranded whales have revealed staggering amounts of plastic debris in their stomachs, contributing to malnutrition, intestinal blockages, and even death. The long-term exposure to toxins associated with these plastics may also impair immune function, reproductive health, and neurological processes, endangering the survival of already vulnerable species.

Beyond the direct physical and chemical harms, microplastics introduce subtle yet profound ecological disruptions. The presence of these particles in the food web can alter species' interactions, competitive dynamics, and overall ecosystem resilience. For instance, reduced fitness in key species like copepods or herring could ripple through the network, affecting predators and prey alike. Furthermore, as climate change and ocean acidification impose additional stresses, the compounded effects of microplastic pollution may push marine systems toward tipping points, with irreversible consequences for biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Addressing the crisis of plastic microparticles in the marine food web demands urgent and multifaceted action. Efforts must include reducing plastic production, improving waste management systems, and developing innovative cleanup technologies. Policy measures, such as banning microbeads and single-use plastics, are critical steps forward. Equally important is advancing scientific research to better understand the fate and impact of microplastics and to monitor their presence across different trophic levels. Public awareness and consumer choices also play a pivotal role in driving change. Only through a concerted global response can we hope to mitigate this insidious threat and protect the health of our oceans from the smallest plankton to the largest whales.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025