In the shadowy corners of global wildlife trafficking, the pangolin has become an unwitting symbol of both ecological fragility and human greed. These gentle, scale-covered mammals, often described as walking artichokes, are being systematically erased from their native habitats across Africa and Asia to feed an insatiable demand for their scales and meat. Despite international protections and growing conservation efforts, the pangolin now holds the grim title of the world’s most trafficked mammal, a status that underscores the profound challenges in combating illegal wildlife trade.

The plight of the pangolin is not merely a conservation issue; it is a complex narrative woven from cultural traditions, economic desperation, and systemic enforcement failures. For centuries, pangolin scales have been used in traditional medicine practices, particularly in China and Vietnam, where they are believed to treat ailments ranging from arthritis to poor circulation. Though scientific evidence does not support these claims, the cultural persistence of these beliefs has created a market that is difficult to dismantle. Meanwhile, the animal’s meat is considered a luxury item, a status symbol served at banquets and elite gatherings, further driving its desirability.

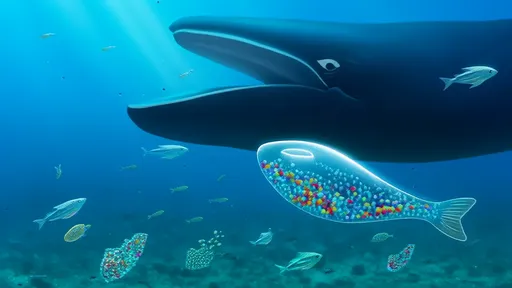

Illegal traders have capitalized on this demand, establishing sophisticated networks that move pangolins from forests in Central Africa or Southeast Asia to markets thousands of miles away. The supply chain is often brutal: live pangolins are poached, stored in cramped conditions, and transported across borders hidden in shipments of other goods. Many do not survive the journey. Those that do face slaughter, their scales carefully removed and packaged for sale. It is estimated that over one million pangolins have been taken from the wild in the past decade alone—a staggering figure for a species that reproduces slowly and gives birth to only one offspring per year.

Conservationists and governments have not stood idly by. All eight species of pangolins are now listed under Appendix I of CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), which prohibits commercial international trade. National laws in many range states have also been strengthened, with increased penalties for poaching and trafficking. Yet enforcement remains a critical weak point. In many regions, wildlife rangers are underfunded, outnumbered, and outgunned by well-organized criminal syndicates. Corruption at border checkpoints and within regulatory agencies further enables the flow of illegal products.

On the ground, conservation groups are working tirelessly to protect remaining pangolin populations. These efforts include anti-poaching patrols, community education programs, and initiatives to rehabilitate and release rescued pangolins back into the wild. Some organizations are also exploring innovative strategies, such as using trained dogs to sniff out pangolin scales in shipping containers or promoting synthetic alternatives to pangolin scales in traditional medicine. However, these measures are often localized and lack the scale needed to counter a global trafficking network.

The challenges are compounded by the pangolin’s elusive nature. Unlike elephants or rhinos, pangolins are solitary, nocturnal, and difficult to track, making population assessments and monitoring exceptionally hard. Scientists still do not have accurate estimates of how many pangolins remain in the wild, which hinders the ability to measure the impact of conservation actions or the escalating threat of extinction.

There is also a growing recognition that demand reduction is just as important as supply interception. Public awareness campaigns in consumer countries have sought to debunk myths about pangolin scales and reduce the prestige associated with consuming their meat. Celebrities and influencers have joined the cause, using their platforms to highlight the pangolin’s plight. Yet changing deeply ingrained cultural practices is a slow and nuanced process, one that requires sustained engagement and sensitivity.

Meanwhile, the COVID-19 pandemic has added another layer of complexity. Some researchers have suggested that pangolins may have played a role in the coronavirus’s transmission to humans, though this remains unconfirmed. This association has led to increased scrutiny of wildlife markets and a temporary ban on wildlife consumption in China. While conservationists hope this could lead to permanent regulatory changes, there are concerns that driving the trade further underground could make it even harder to track and combat.

The story of the pangolin is a microcosm of the broader wildlife trafficking crisis, reflecting the intricate interplay between ecology, economics, and culture. Saving this species will require more than just laws and patrols; it will demand a global shift in how we value natural heritage and biodiversity. International cooperation, community involvement, and innovative conservation strategies must converge to create a future where the pangolin is no longer a commodity but a thriving part of the world’s ecosystems.

Time is running out. With each pangolin taken from the wild, the species moves closer to the brink. The world must decide whether it will allow this unique creature to vanish forever or rally to ensure that future generations might still witness the curious, scaly anteater shuffling through the forests under the cover of night.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025