In a quiet laboratory in South Korea, a beagle puppy takes its first clumsy steps. To the casual observer, it appears like any other newborn dog—playful, curious, and utterly endearing. Yet this puppy represents something far more profound: it is the genetic duplicate of a beloved pet that passed away years earlier. This is the reality of pet cloning, a technology that has evolved from science fiction to commercially available service in just over two decades. As companies around the world now offer the chance to replicate a cherished animal companion for prices ranging from $50,000 to $100,000, society finds itself grappling with a complex web of scientific achievement, emotional longing, and ethical unease.

The science behind pet cloning is both fascinating and remarkably similar to the process that created Dolly the sheep, the world’s first cloned mammal, in 1996. The most common technique used is somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). It begins with the collection of a small skin tissue sample from the animal to be cloned, ideally taken shortly after death or even during the pet’s life and preserved in a gene bank. From this sample, scientists extract the nucleus of a somatic (body) cell, which contains the complete genetic blueprint of the donor animal. Meanwhile, an egg cell is harvested from a donor animal of the same species. Its nucleus, and thus its genetic material, is carefully removed, leaving an empty shell ready to receive new instructions.

The critical moment comes when the nucleus from the pet’s cell is inserted into this enucleated egg cell. A carefully controlled jolt of electricity fuses them together and triggers the egg to begin dividing, just like a naturally fertilized embryo. This developing embryo is then implanted into the uterus of a surrogate mother animal, who, if the procedure is successful, will carry the pregnancy to term and give birth to a clone. The resulting animal is a genetic twin to the original pet, born at a later date.

Proponents of the technology hail it as a monumental scientific breakthrough with profound implications. For grieving pet owners, cloning offers a seemingly miraculous solution to heartbreak. The bond between humans and their pets can be incredibly deep, often comparable to that of family members. The death of a dog, cat, or horse can leave a void that feels impossible to fill. Cloning provides a unique form of solace—the promise of restoring not just a similar pet, but one that carries the exact same genetic identity. This can feel like a second chance, a way to cheat time and loss. Beyond the emotional appeal, cloning technology also holds promise for conservation, offering a potential tool to resurrect endangered or even extinct species by preserving genetic diversity.

Furthermore, the research and development driving pet cloning have significant spillover benefits for veterinary and human medicine. The processes involved have advanced our understanding of stem cells, genetic diseases, and reproductive biology. Techniques refined in animal cloning labs contribute to broader scientific endeavors, including the development of new medical treatments and the preservation of valuable genetic lines of working animals, such as elite police dogs or search-and-rescue heroes.

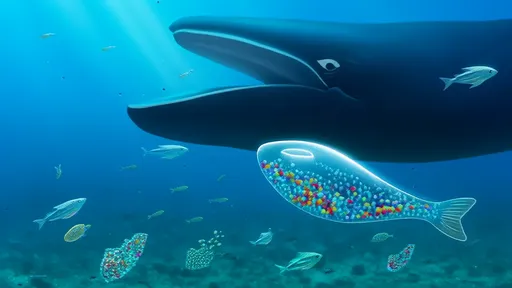

However, this scientific marvel is shrouded in a thicket of ethical concerns that cannot be ignored. The most immediate and visceral criticism revolves around animal welfare. The cloning process is notoriously inefficient. It often requires the harvesting of eggs from numerous donor animals and the implantation of multiple embryos into several surrogates to achieve a single successful pregnancy. Many embryos fail to develop, and surrogates undergo invasive procedures. Critics argue that this subjects a significant number of animals to suffering and medical risk for a non-essential human desire, raising serious questions about our moral responsibility towards other creatures.

Another profound ethical dilemma lies in the very promise sold to consumers: genetic replication. While a clone shares the DNA of its predecessor, it is not the same animal. Personality, temperament, and even appearance (like coat patterns in cats, which can be influenced by the uterine environment) are not solely dictated by genes. They are shaped by a complex interplay of genetics, epigenetics, prenatal conditions in the surrogate mother, and, most importantly, unique life experiences and upbringing. The cloned puppy will not remember its former life or its owner. This leads to a dangerous potential for misunderstanding and heartbreak when a new pet, despite looking identical, behaves differently. Ethicists warn that this commodification of life, reducing a complex being to a replaceable genetic product, fundamentally misunderstands the nature of relationships and individuality.

The significant financial cost also introduces questions of accessibility and priority. In a world where millions of healthy animals are euthanized in shelters each year due to overpopulation, is it ethically justifiable to spend vast sums of money to create a single new animal? Critics contend that these resources could be better directed toward supporting shelter systems, promoting spay/neuter programs, and improving animal welfare on a larger scale. The practice, they argue, caters to the wealthy and exacerbates a disconnect in how society values different lives.

Looking forward, the conversation around pet cloning is likely to intensify. The technology will almost certainly become more efficient and potentially less expensive, making it accessible to a wider audience. This expansion will force a broader societal reckoning. There is a pressing need for robust regulation to ensure the humane treatment of donor and surrogate animals involved in the process. Furthermore, the industry demands complete transparency with clients, ensuring they understand that they are purchasing a genetic duplicate, not a resurrection of their old friend with its memories and experiences intact.

Ultimately, pet cloning sits at a uncomfortable crossroads between our deepest emotions and our highest scientific ambitions. It is a testament to human ingenuity and our powerful desire to hold onto those we love. Yet, it also serves as a mirror, reflecting difficult questions about our relationship with the natural world, the ethics of creation, and the true meaning of life and individuality. The puppy in the South Korean lab is indeed a scientific marvel, but it is also a living, breathing question—one that society is only just beginning to learn how to answer.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025